Remembering the Economy Runs of the 1980s

As I drove the Honda Insight towards Skudai, memories of my participation in economy runs in the early 1980s kept coming into my mind. Back then, fuel economy was thought to be a significant aspect of motoring and for cars which were proven to be economical, large figures were splashed on the advertisements – I remember the 2nd generation 1.0-litre Charade then boasting of a fuel consumption of 19.4 kms/litre (55 mpg) which was quite impressive.

The Royal Perak Motor Club (RPMC), a small Ipoh-based club, organised some economy runs between Ipoh and Singapore and in the first year, the response was good. It was a challenging event and yet anyone could take part without having to spend a lot of money to modify the car. The concept of the contest was just to drive as economically as possible.

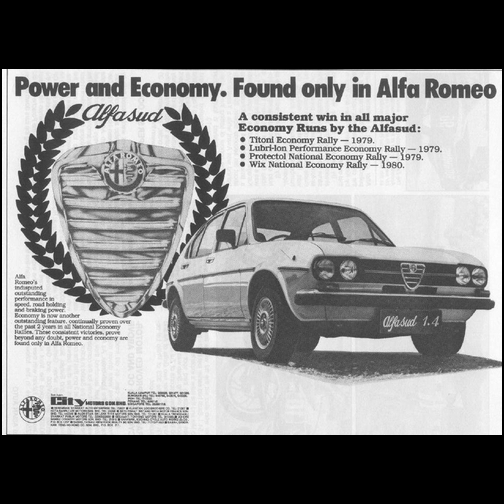

In the second year (1980 or 1981), the leading car companies took an interest in the event and fielded ‘official works teams’. The main contenders were Nissan (Tan Chong), Toyota (Borneo Motors, the franchise holders then), Mitsubishi (C&C Malaysia), Mazda (Asia Motors, the franchise holders then), and Honda (Kah Motors in Malaysia and Singapore). City Motors also entered a team of Alfasuds, partly because the owners were from Ipoh and wanted to give their support to the club. As some of these companies were already active in rallies, they got their rally drivers to enter the economy runs, something which did not really go down well with the drivers but they agreed since their sponsored drive depended on their cooperation!

The first economy run I entered was from Ipoh to Singapore and I was in a Mitsubishi Lancer SL with Garry Chua. It was a different experience from rallying as the pace was really slow. But my role as navigator was still pretty hectic as it required, besides navigating, constantly recalculating the average speed needed and time left to the checkpoint. There was no laptop in those days so it was just with a basic Casio calculator under a dim lamp.

While the Insight drive had no specific time of arrival at a checkpoint, which meant that a snail’s pace could be applied, the economy runs had fixed times for getting between two points which required a moderate speed (as high as 70 or 80 km/h). So if the speed was too slow, you had to drive faster and that burnt more fuel. Worse, if you encountered a traffic jam, pressure would build up as the average speed to the checkpoint increased every minute you were delayed. I remember that there were times our average speed rose to 100 km/h and the thought of so much fuel being consumed was ‘painful’. But if you arrived late, you also got penalised with ‘extra fuel lost’ so it sometimes required a decision whether to drive faster and burn more fuel or arrive a bit late and take a penalty.

There were different strategies to get the lowest possible fuel consumption. A light right foot was important but some also coasted in neutral where possible and planned their drive up slopes carefully. Because every moment stopped meant wasting fuel, there were times when drivers refused to stop and that made things rather hairy. Some drivers, when coming up to a jam, would suddenly veer to the left and bump along the grass so as not to stop at all! But all of us ran with our windows up to reduce drag; it was okay at night but got pretty uncomfortable in the afternoon.

The runs usually started late in the evening and would not finish till the following afternoon so it was a gruelling drive with no sleep too. There was no N-S Expressway then and the route went along the coastal road and some sections even went through rubber estates!

Once the official teams began taking part, competition became more serious and the ‘works teams’ had the money and personnel to prepare the cars for the purpose. The cars were supposed to be ‘standard’ but carburettors (virtually no EFI engines then) could have their jets changed and tyres could be inflated to very high pressures to reduce rolling resistance. There were some ‘secrets’ which the mechanics in each team were said to know but wouldn’t tell and everyone speculated that there were people who used Singer sewing machine oil in their rear axles! Scrutineering was also quite strict and the cars and occupants were weighed to ensure that there was no unusual lightening. In any case, the system of calculation took into account the car’s weight as a factor.

I did a run with the Toyota team in 1981 but the Corolla KE70’s 1.3-litre OHV engine wasn’t quite the right type of engine for such driving and Borneo Motors didn’t continue their effort after that year. So I went back to the Mitsubishi team which used Galants, Tredias and the Colt Supershift. The Colt’s unique Supershift gearbox had two gear ranges – Performance and Economy – which could be engaged as desired. This was useful for the economy run and helped Mitsubishi win the manufacturer’s trophy in the final year that economy runs were held.

The economy runs were discontinued because there were too many allegations of cheating. The organisers had done their best to prevent cheating but somehow, people seemed to still be able to cheat. I think the first time cheating was believed to have taken place was when someone tried to bluff the others about how little fuel his car had used from Ipoh up to Kuala Kubu Baru. It was some ridiculous amount and word spread that he had cheated. This triggered off suspicion and during the night, the other teams plotted to find ways to beat that guy.

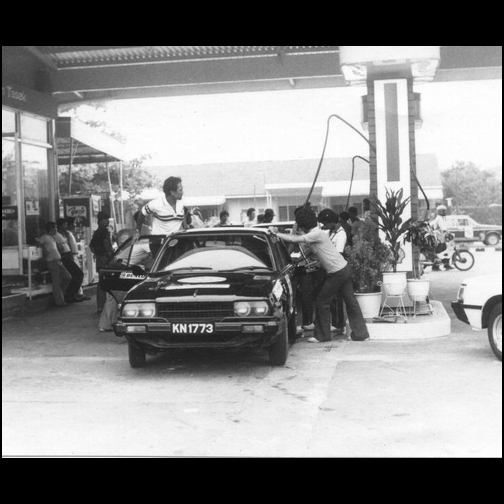

The efforts to prevent cheating were ridiculed by one team when one of its cars, upon reaching the petrol station in Singapore, had petrol overflowing when the driver uncapped the tank! The point was that in spite of the policing, people were still able to cheat. Those cars which were hatchbacks with an easily accessible boot were also suspected because there was a way to reach the fuel tank hose.

In 1982, the organisers tried a new approach to preventing cheating. They had every contestant bring along a few ‘observers’ who would sit in another car. That way, no one would be able to do anything illegal like refuelling along the way without anyone knowing. And even then, the allegations of cheating – and even sabotage – continued and Chew Tee Wong, manager of the Mitsubishi team, expressed his great disappointment at the state of affairs and declared that Mitsubishi would case to participate. His statement seemed to influence the other teams to pull out and much to the sadness of the RPMC, the economy runs lost popularity.

What sort of consumption was achieved? From the records I was able to dig up of the 1981 run, the Alfasud 1.4 was the winner that year with 28.592 kms/litre (80.7 mpg) although, as I said earlier, the weight of the car was also factored in. But the Honda team won the manufacturer’s title with its trio of CVCC Accords. Ex-Mitsubishi manager Chew told me that the Colt won in the final year of the economy runs and returned 25.4 kms/litre (72 mpg). He should have a good recollection since he was the one behind the wheel!

The economy runs were certainly interesting and provided some sort of challenge. But I doubt if Malaysian motorists really cared too much about the results. Today, fuel consumption is hardly discussed and would not influence someone to buy a car. It is generally taken for granted that for a given engine size, there is a certain range of fuel consumption. The manufacturers offer some factory figures to refer to but they are done in controlled conditions so they are optimum. The average motorist may not get such good figures since town driving these days involves a lot of stopping, crawling and having the air-conditioner on most of the time.

But it is nice if you can have a car as economical as the Honda Insight which can easily do 35 kms/litre without driving ‘economy run style’!

Chips Yap